Sanjay Kumar

Culinary Semiotics in the Hindi Films of Ritesh Batra

Abstract

In his work, Terry Eagleton states that food goes beyond mere sustenance, functioning as a multifaceted signifier. Like post-structuralist texts, food unfolds the possibility of endless interpretation, incorporating multiple meanings such as gift, threat, poison, recompense, barter, seduction, solidarity, and suffocation. This semiotic dimension within the context of filmmaking is extensively explored in Reel Films: Essays on Food and Film, edited by Anne L. Bower. The principal objective of this article is to analyse the function of food as a complex signifying system in two Hindi films directed by Ritesh Batra: The Lunchbox and Photograph. In both films, the quotidian act of eating becomes visually and aesthetically significant. In The Lunchbox, the journey from food to love is portrayed through the carefully and affectionately prepared dishes by Ila, the female protagonist. On the contrary, in Photograph, the narrative depicts a journey from love to food, as Rafi, the male protagonist, decides to launch a Campa Cola bottling plant for the sake of his beloved, who is nostalgic about this beverage. The presence of food is explicitly incorporated in the title of the film The Lunchbox, where Ila as a housewife, cooks at home, and Sheikh, who has experience of having worked in a restaurant. The most prominent settings include Ila’s kitchen and the office canteen where Sajan and Sheikh sit to have lunch. Though not in the same degree, both films present the process of food preparation and the pleasure derived from its consumption. An unexpected turn, a misdelivered lunchbox, triggers a long-distance romance between two complete strangers. Through the strategically placed culinary scenes, both films not only carry their respective narratives forward but also delicately illustrate a tapestry of emotional landscapes and social hierarchy of their characters. While The Lunchbox can be arguably classified as a food-centric film, Photograph employs food as a plot device, setting, and metaphor.

In his seminal work Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Roland Barthes asserts that “we could classify novels according to the frankness of their alimentary allusions: in Proust, Zola, Flaubert, we always know what the characters eat; in Fromentin, Laclos, or even Stendhal, we do not. The alimentary detail goes beyond signification; it is an enigmatic supplement of meaning (of ideology)” (125). Following Barthes’ framework, it is possible to extend this classification to films, evaluating them on the basis of the explicitness of their alimentary references. In fact, one of the first films made by the Lumière brothers in 1895, Repas de bébé, depicts a baby being spoon-fed by the father while the mother prepares and drinks tea. However, until the end of the 20th century, very little attention had been paid to the role of food in films. A cursory examination of Ritesh Batra’s films, The Lunchbox (2013) and Photograph (2019), reveals a special focus on culinary references.

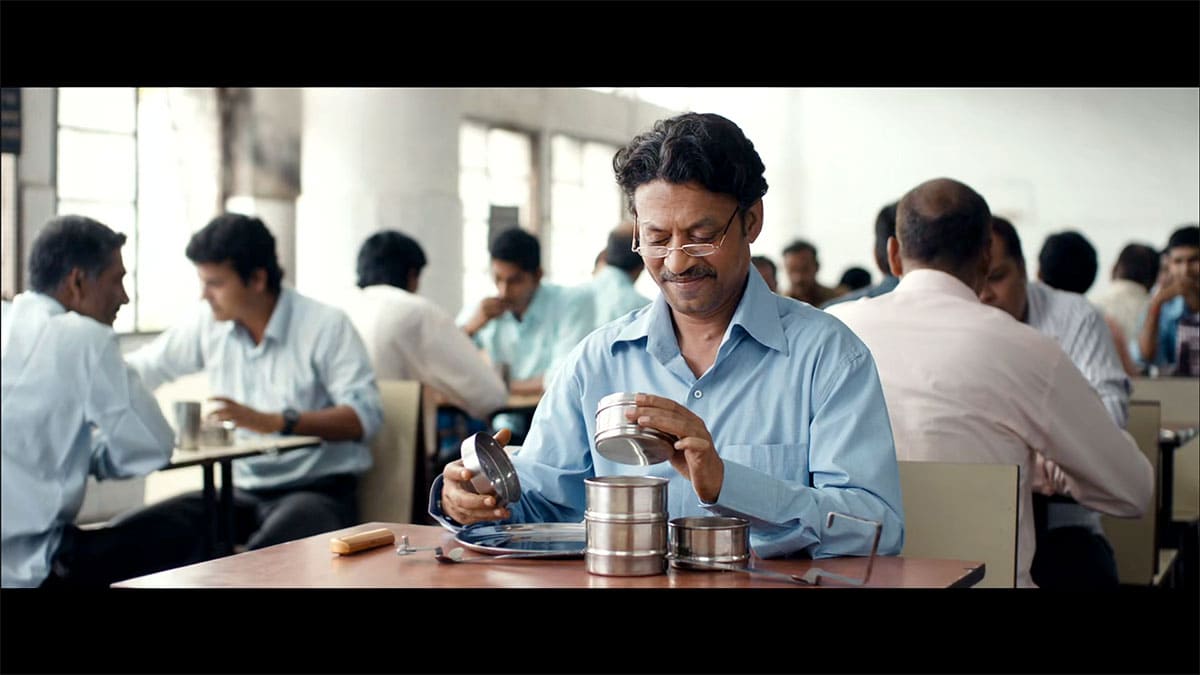

The main objective of this article is to explore the role of food within the narrative structures of these two Hindi films. Let us ask this question at the outset: Can they be categorized as “food films”? Unlike Photograph, in The Lunchbox, food is not used merely as a narrative element; it provides a solid foundation for the visual and thematic construction of the film. It is visible in the film’s title itself, which gives primacy to the food, with Ila (Nimrat Kaur), a housewife, and Sheikh (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), a former professional cook, as crucial characters. Further, vital settings such as Ila’s kitchen and the canteen where Saajan (Irrfan Khan) and Sheikh share meals reinforce the culinary presence. The camera never ceases to highlight the food preparation, presentation, and consumption; in close-ups, food fills the screen. We notice food in multiple forms: delicious, too salty, or spicy, and observe its multiple receptions—consumed completely, partially, rejected, or shown indifference.

According to Terry Eagleton, food rises above its biological function of nutrition, working as a multi-layered signifier: “If there is one sure thing about food, it is that it is never just food. Like the post-structuralist text, food is endlessly interpretable, as gift, threat, poison, recompense, barter, seduction, solidarity, suffocation” (1). This semiotic richness is rigorously examined in Reel Films: Essays on Food and Film, edited by Anne L. Bower. The objective of the current analysis is to explore how food functions as a complex signifying system in Batra’s The Lunchbox and Photograph. On the one hand, in The Lunchbox, the narrative progresses from food to love explicitly showing the mouth-watering dishes prepared by Ila. On the other hand, in Photograph, the trajectory from love to food is portrayed through Rafi’s plan to establish a Campa Cola factory for the sake of his would-be partner. These culinary moments do not appear as mere plot devices but have deep emotional and social significance, reflecting the characters’ psychology and their social standing.

Therefore, this analysis is being carried out in three steps: firstly, food as a plot device, then food as characterization, and lastly, food as a site of gender and social class. We will start by looking at selective food scenes in which certain new information is revealed or important decisions are made that advance the plot. The setting and context in which food is presented can carry the story forward. Then, we will get a glimpse of food reflecting and reinforcing the depth and nuance of the characters. The protagonists’ gastronomic journey may be revelatory of their emotional state, cultural identity, and personal growth. After that, we explore the intersections of food, gender, and class, highlighting how culinary experiences indicate social roles and cultural standards. Food scenes manifest social hierarchy through dining etiquette and habits.

Food as a Narrative Catalyst

The Lunchbox offers an insightful examination of Mumbai’s intricate lunch delivery system, wherein freshly prepared hot meals are collected from homemakers or restaurants and delivered to office workers. This process is executed by dabbawallas, who collect the lunchboxes in the late morning and return them empty in the afternoon. The lunchbox itself acquires a status of utmost importance, competing with that of the characters. It has its own noticeable identity, with no. “11F2″ inscribed on its cover. The opening sequence of the film depicts various lunchboxes being transported via cart and train, initially in brief glimpses and subsequently in more elaborate detail. The journey of the lunchbox catches our eyes as much as Saajan and Sheikh do. The lunchbox dispatched by Ila, the housewife, intended for her husband Rajeev (Nakul Vaid), is distinguishable by its green cover. Ila performs the socially scripted role of a conventional nourisher, trying hard to ensure her marital happiness by providing her husband with home-cooked, delectable dishes. As Terry Eagleton asserts: “Food looks like an object but is actually a relationship…” (1). The film meticulously portrays Ila in her kitchen, passionately engaged in cooking, smelling, and tasting to ensure the quality of her dishes, even implementing the instructions of her affectionate neighbour, Deshpande Auntie (Bharti Achrekar), who is a resident of the floor above. Thus, the film’s opening showcases the aesthetic, olfactory, and gustatory attributes of food, hinting at its broader symbolic significance. When Ila’s intense passion for preparation resonates with an overwhelming passion for consumption, it leads to a gastronomic adventure that gets transformed with a passage of time into a romantic adventure. As Ernest Hemingway articulates: “I have discovered that there is romance in food when romance has disappeared from everywhere else. And as long as my digestion holds out, I will follow romance” (376).

By chance, the lunchbox packed by Ila lands up on the desk of Saajan Fernandes, an experienced accountant and a middle-aged widower on the verge of retirement. The male protagonist perceptively observes the lunchbox, paying particular attention to the neatness of its cover and the steel containers within. Exactly like a connoisseur, he smells and tastes the food. Once having realized her mistake, Ila explains it through a letter placed in the lunchbox the next day. By exchanging a series of messages, they develop a certain understanding of each other’s situations and start empathizing with each other. In a subsequent scene, Saajan eagerly clutches at the lunchbox upon its arrival, inhaling its aroma through the green cloth cover, an action that appears peculiar to his curious colleague sitting next to him. Saajan then declares, it is time for lunch, despite the office clock showing 1:07 PM and his colleagues still working, hinting at his impatience to eat and his impatience to read Ila’s response enclosed within the lunchbox. On the contrary, while opening the polythene bag at home to take out the ordered food, he looks indifferent, indicating that it will satiate only his physiological need, devoid of gustatory pleasure.

Fig. 1 – Saajan enjoying the food prepared by Ila, still from The Lunchbox (2013).

In the following scene, Saajan’s face evinces visible disquiet after tasting the excessively spicy food. After having received the lunchbox, Ila immediately estimates its weight and guesses that the food has not been fully consumed. The letter placed inside records Saajan’s dissatisfaction in the following measured words: “Dear Ila, the salt was fine today. The chili was a bit on a higher side. But I had two bananas after lunch. They helped to extinguish the fire in my mouth. And I think it will also be good for the motions. There are so many people in the city who eat a banana or two for lunch”. Ila’s sleep disturbance at night indicates her repentance over the immoderate use of chili, compounded by her husband’s late arrival from the office. This moment marks the beginning of Ila confiding in Saajan about her concerns regarding Deshpande Auntie’s life and her own marital life. Thus, through a quirk of fate, the misplaced lunchbox gives birth to a platonic relationship between two strangers, Ila and Saajan.

A comparison of the lunch scene in the office canteen with the evening scene at Saajan’s residence is especially revealing. In the latter, Saajan unpacks his modestly wrapped food from polythene bags and immerses himself in a book, displaying scant regard for the meal. Next day, his smile reflects his anticipation of a palatable lunch. Ila’s neighbour, alerted by the first whistle, contributes spices via a basket suspended from the balcony. Ila is depicted meticulously garnishing and packing the lunchbox. Upon receiving the lunchbox, inhaling the aroma of the food after removing the cloth cover has become a daily ritual for Saajan. Even Sheikh is crazy about the aroma emanating from Saajan’s lunchbox, remarking, “Your lunchbox has a wonderful smell. I could taste the food without eating it.” It reminds us of Immanuel Kant declaring, “The smell of food is so to speak a foretaste” (51). The German philosopher further elaborates, “Smell is taste at a distance, so to speak, and others are forced to share the pleasure of it, whether they want to or not” (50). Kant asserts, “The senses of taste and smell are both more subjective than objective… Both senses are closely related to each other, and he who lacks a sense of smell always has only a dull sense of taste.” (49) The pervasive scent of food is a recurring motif in the film. The boss notes exasperatedly that files handled by Sheikh are permeated with the fragrance of vegetables, onions, potatoes, and garlic, as Sheikh has been chopping vegetables on his office files.

Fig. 2 – Saajan having dinner halfheartedly at home; still from The Lunchbox (2013).

When Sheikh gets reprimanded by the boss for his catastrophic errors in calculation, Saajan comes forward generously to take responsibility, thereby protecting Sheikh from dismissal. However, Saajan takes Sheikh to task over the smelly files and asks him to leave. Admitting his mistake, Sheikh apologizes and invites Saajan to relish pasanda at his place. This scene depicts the potential of food serving as a tool for conflict resolution. Shakespeare has similarly employed the offering of food in his plays for this purpose. For example, in Henry V, Lieutenant Bardolph attempts to reconcile Corporal Nym and Ancient Pistol by inviting them to breakfast: “I will bestow a breakfast to make you friends, and we’ll be all three sworn brothers to France. Let’t it be so, good Corporal Nym” (act 2, sc. 1). Beyond its function as a reconciliatory gesture to move the plot along, a meal scene can reveal essential details. Lindenfeld and Parasecoli assert in this connection: “Commensality, from dinners to drinks at a bar, offered filmmakers and scriptwriters the opportunity to have their characters convene and talk with each other, providing important information about themselves and the story” (7). In the film Photograph, a significant amount of conversation and decision within the Shah family happen at the dining table, the sole occasion for the family gathering. During these meals, when the whole family is present, we are made aware of Miloni’s childhood interest in theatre and the plan regarding her marriage. Similarly, in The Lunchbox, the dinner scene where Saajan is invited to taste pasanda is highly significant. At the residence of Sheikh and Meherunissa (Shruti Bapna), Saajan shares his romantic interest in Ila with the couple. Sheikh narrates the story of his elopement with Meherunissa due to her father’s opposition to their marriage and requests Saajan to act as his guardian, given his orphaned status since childhood. This occasion fosters a unique bond between Saajan and Sheikh. Saajan announces his decision to forgo early retirement. However, once he learns that Sheikh’s prospective father-in-law is willing to gift him a scooter for his promotion, he reconsiders his decision which is revealed in a later scene. Sheikh, too, exhibits no disappointment upon hearing that Saajan is not retiring, despite the fact that Saajan’s extended employment creates an obstacle to Sheikh’s promotion. Both characters willingly sacrifice their personal advancement for each other’s well-being.

In Photograph, the first meeting between Rafi’s grandmother and Miloni takes place in a restaurant where the grandmother is shown eating a type of soup while Rafi and Miloni have soft drinks before them. The grandmother’s dialogue is used to sketch a portrait of Rafi. Later, the grandmother’s comment is used to reveal, as we don’t see this through the lens of the camera, that Miloni is hesitant to accept the grandmother’s offer of food. This act is interpreted as standoffish and criticized by the grandmother. As Anke Klitzing, a lecturer in Gastronomy and Food Studies, asserts: “Eating together creates and maintains social bonds; it can be used as a sign of inclusiveness or exclusiveness” (27). In another scene, during a rainstorm, Miloni and Rafi stand on the road waiting for a taxi, and Miloni proposes they have tea. By providing an intimate setting, this moment serves as an opportunity for further openness. Rafi wants to know why Miloni keeps on refusing to have soft drinks. Miloni replies that her grandfather used to treat her with Campa Cola during her childhood. But following her grandfather’s death and the company’s closure, she no longer feels like having any other soft drink. Rafi recalls how his father would treat him to kulfi at the end of every month, a ritual he has continued. Thus, the act of eating kulfi now serves not only as a means of reliving those childhood experiences but also as a homage to his father’s legacy. Both examples show how parents and grandparents shape children’s food preferences. Besides, the association of food with memory is profoundly significant, offering not only an insight into the circumstances that have shaped their lives but also illustrating a growing connection between them. From the audience’s perspective, it deepens our understanding of the characters and makes us empathise with the protagonists.

Food as Characterization

According to Charlotte Boyce, “Throughout literary history, food has been intrinsic to articulations of identity. […] the semiotics of consumption – what, how and where characters eat – reveal much about individual subjectivities and collective identities” (248). In other words, the semiotic analysis of preparation and consumption patterns of food offers a significant insight into different identities. This section, therefore, seeks to throw light on the intricate relationships each character maintains with food, whether through its preparation or consumption. Farb and Armelagos assert, “All animals feed but humans alone eat. A dog wolfs down every meal in the same way, but humans behave in a variety of ways while eating” (3). So, humans, driven by more than mere instinct and hunger, have elevated eating into a rich social experience and a profound form of personal expression.

Preparing ancestral recipes is a source of cultural pride and continuity and a way to honour one’s roots. In The Lunchbox, Ila, the female protagonist, is a young housewife with an intense passion for cooking. She is extremely delighted to discover her maternal grandmother’s notebook containing a handwritten recipe for spring apples. Respecting her culinary heritage, she follows instructions from this notebook and prepares a dish for Saajan. Similarly, in Photograph, Rafi’s cousin is appreciated for her culinary skill. This is shown through scenes depicting Rafi and his friends eating biryani with relish at her house. Sharing biryani is integral to their cultural background, and it allows them to feel connected in a metropolitan city like Mumbai.

Fig. 3 – Rafi drinking with his friends on the floor; still from Photograph (2019).

More than just nourishment, dining has often been considered a social activity, as a way to bond and strengthen relationships. To dine in solitude is to lose the invaluable chance for intellectual exchange and discourse. It is well-documented that Immanuel Kant, the eminent philosopher of the Enlightenment, regularly shared meals with his friends. He eschewed the notion of reducing the act of eating to the mere satisfaction of bodily needs. He asserted that communal dining fosters a richer, more meaningful experience, thus advising against solitary consumption for this very reason. He states, “Eating alone (solipsismus convictorii) is unhealthy for a scholar who philosophizes; it is not restoration but exhaustion (especially if it becomes solitary feasting): fatiguing work rather than a stimulating play of thoughts” (180-181). Thus, Kant revealed a significant relationship between intellectual well-being and dietary habits. Seen from this perspective, Saajan’s solitary eating is as much a cause as an effect of his solitary lifestyle. In the canteen, the camera focuses on an empty seat across the table from Saajan, while everyone else chats and eats together. This scene reinforces the protagonist’s social isolation. As Eagleton affirms, “Snatching a meal alone bears the same relation to eating in company as talking to yourself does to conversation” (2). When Saajan buys a cigarette, he does not bother to share it with Sheikh, who has to buy one for himself. Saajan quietly escapes after giving an appointment to Sheikh at 4:45 p.m., smoking alone on his balcony and watching his neighbours dining together through the window. When a little girl catches him observing, she closes the window. This scene is repeated towards the end of the film, but this time the little girl waves to him instead of closing the window. This scene announces a change in Saajan’s personality; he no longer chides children for playing cricket around his flat. The non-diegetic music in the background provides insights into the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings, perhaps hinting at a desire to end his loneliness by starting afresh a family life.

When Sheikh invites Saajan to eat pasanda at his place, Saajan accepts the proposal but postpones the visit on the pretext of being busy for the time being. However, it is evident that at home, he does nothing but watches old serials and smokes on the balcony. He hardly goes out with friends or interacts with neighbours. A turning point in his life occurs when he begins sharing food with Sheikh. When they come around the table, they do not just share food, they also share their experiences. The audience notices the benefits of sharing and its transformative power. Having already smelled the food, Sheikh finds his pleasure greatly enhanced upon tasting it and expresses a desire to order the same dish for himself. Sheikh remarks, “You need magic in the hands. Anyone can make food but you need magic”.

In contrast, Rafi, the male protagonist of the film Photograph, is not as lonely as Saajan Fernandes from The Lunchbox. Even if Rafi is a little shy, he lives with several roommates and often shares meals and drinks with them. His grandmother recalls that Rafi organized a lavish feast at his sisters’ weddings, offering such delicious samosas that guests not only enjoyed them but also hid some in their pockets. Even after being told about this incident, Rafi requested his grandmother not to stop them. This attitude towards food at the feast displays his sense of hospitality and generosity. Besides, celebratory meals create memories which last a lifetime.

Our responses to food can reflect our overall behaviours, attitudes, and personality traits. Rajeev, Ila’s husband, seems to be unconcerned about the quality of food. He shows the least interest in discussions about the food; rather, he is absorbed in making calls on his mobile and watching television at home. In a dinner scene, when he comments on the table, Ila initially assumes it pertains to the meal, but he is actually referring to the program on the screen. As Ila’s neighbour observes, Rajeev ate someone else’s food without even remarking on the difference. This incident leads to a comic situation at his expense. Saajan praises the food to the canteen boy, mistakenly thinking it originated from the canteen. The verbal and non-verbal reactions of the canteen boy make it evident that Saajan praises his food for the first time. Surprised by the unexpected appreciation, the canteen boy begins to supply the cauliflower dish more frequently. In reality, because of a mix-up, the canteen lunchbox goes to Ila’s husband every day, who, fed up with its repetition, complains of stomach discomfort. Though the camera shows Rajeev in a cheerful mood, chatting with his co-passengers in the train, yet he barely exchanges words with Ila at home. Contrary to this attitude, Saajan frankly replies to Ila’s first letter with, “Dear Ila, the food was very salty today.” He observes and comments on the minute details of the meal with the same keen eye he uses for accounting. In one of the scenes, his boss acknowledges that Saajan has never made a single mistake in 35 years. On several occasions, he fully enjoys Ila’s food, paying attention to its sensory properties: appearance, texture, aroma and taste. This reveals that he not only appreciates life’s little delights but also understands and values the effort involved in cooking.

In Photograph, Miloni’s nephew is scolded for not eating properly, and this attitude is immediately correlated to the recklessness he shows towards his studies. Thus, his approach towards his studies is echoed in his manner of eating, signalling malnourishment in both a literal and intellectual sense. Food is supposed to not only nourish our body but also feed our soul.

Sheikh, a professional cook who has the experience of working in a Saudi hotel, is depicted in a scene cutting vegetables on his suitcase while on a train. He explains that he optimizes his time by completing half of the meal preparation during the journey. He loves cooking for his girlfriend, Meherunissa, who joins him in the evening. It’s a tangible representation of his care and affection for his partner. Sheikh narrates how he used to manage cooking, room service, cleaning, and accounting in Saudi Arabia. The centrality of food in the socialization process is evident. When Ila proposes meeting Saajan for the first time, it is at Kooler Café, renowned for its keema pao, her favourite dish. Food has an unparalleled ability to foster connections and build trust.

In the film Photograph, the male protagonist Rafi’s close friend, who is also a photographer like him, advises him to get married. He believes that it is a way to fully enjoy his life and attain happiness. This well-being, as explained further by his friend, includes activities such as a trip to the zoo with children and eating golgappa, a popular snack and street food. On the contrary, Rafi not only rejects altogether this idea but also cautions him against falling in this trap. According to Rafi, the quest for a marital bliss will convert his friend into a “softie” like their roommate, Zakir Bhai. The Cambridge Dictionary defines “softie” as “a kind, gentle person who is not forceful, looks for the pleasant things in life and can be easily persuaded to do what you want them to do”. Actually, Zakir Bhai’s wife and children live in the village, and he keeps on missing them. His meagre income doesn’t allow him to rent a room or flat for his family in the expensive metropolitan city of Mumbai. So, despite being married, he can’t afford the luxury of living together with his family. Quite often, he becomes emotional while recalling the unfortunate circumstances under which Tiwari, his former roommate had to commit suicide. The term “softie” acquires a deeper symbolic meaning when it is amusingly defined by a clerk at the window as something similar to ice cream but not as hard as kulfi, rather so soft that it melts in the mouth. Then, Rafi’s friend wonders what the point is in eating something that melts as soon as it is put in the mouth. We may conclude that being sentimental about family life with a life partner and children is clearly disapproved of by Rafi and finally by his friend. In the next scene, both are found eating kulfi in the street. The reference to food transforms the simple term “softie” into a metaphor that allows us to theorize about different personality types.

Through Zakir Bhai’s character, we can deduce that Rafi classifies people into two types: those who are like kulfi (hard, unsentimental, and pragmatic) and those who are like softie (soft, emotional and romantic). When Zakir Bhai suggests that Rafi get married and settled in life, Rafi responds, “Zakir Bhai, I am not a softie like you. I am tough like kulfi. Kulfi.” Ironically, Rafi, who boasts of being a kulfi-type person, falls in love and gradually transforms into a “softie”. This transformation is beautifully hinted in another scene of the film, where Rafi goes to the kulfi vendor from his village. The vendor informs Rafi of his decision to stop the kulfi business and purchase a softie machine. At this point, the audience presumes that Rafi is mentally prepared to start a family life and is making all efforts to impress Miloni, who hails from a higher social class.

Food as Representation of Gender and Social Class

Culinary practices are closely linked to gender roles, revealing societal expectations, cultural values, and traditions. As Farb and Armelagos assert: “Eating is intimately connected with sex roles, since the responsibility for each phase of obtaining and preparing a particular kind of food is almost always allotted according to sex” (5). In a patriarchal society, it is primarily the responsibility of women to pass on their culinary knowledge and skills to the next generation of women. For instance, in The Lunchbox, Deshpande Auntie orally transmits innovative and exciting recipes to Ila. Although her face is never shown on camera, her voice is heard advising Ila to eat soaked almonds to strengthen her memory. She provides guidance to Ila on the selection and quantification of spices to be used in food preparations. The recipe notebook of Ila’s maternal grandmother serves as a valuable source of written knowledge, passed down to the next generation. The recipes of Deshpande Auntie or the grandmother are designed to generate a sense of cheerfulness and well-being in Ila and those within her social circle. In fact, one of the most renowned aphorisms articulated by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1855), an esteemed figure recognized for authoring a celebrated work on gastronomy, is: “The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a star” (n.p.). Ila’s source of inspiration is not limited to her neighbour and grandmother’s recipes; she listens regularly to radio programs on compelling recipes. In one of the initial scenes, the recipe for the “all-time favourite Paneer Do Pyaza” is discussed. At a crucial moment in the film, it is revealed that Ila’s mother dedicated a considerable period of her life to an unhappy marriage, wherein she sacrificed her own desires to fulfil the needs of her husband. She experiences a profound sense of relief following her husband’s death, frankly expressing her craving for parathas. She had skipped her breakfast that morning in order to prepare food for her husband. She confides, “I was always worried about what would happen to me when he passed away. … But now I just feel hungry. In the beginning, there was a lot of love between us, when you were born. But for several years, I have been disgusted by him. Every morning, his breakfast, his medicine, his bath… breakfast, medicine, bath”. This disclosure helps Ila in deciding to come out of her suffocating conjugal life and search for happiness in Saajan’s company.

Divergence in food consumption by social class mirrors differences in an individual’s social privilege and power. In The Lunchbox, in one of his letters to Ila, Saajan writes about the compulsion of some individuals to limit themselves to bananas for lunch due to their low income. In the film Photograph, Rafi, the struggling street photographer, and his roommates are depicted drinking and conversing on the floor in a relaxed and informal way. Then, the camera shifts to a dining scene in the Shah household. The Shah family can afford to employ a full-time cook and flaunt their gastronomic ostentation in front of their guests. Here, the family cook is appreciated for her culinary skills, and a child is warned to eat properly. The family follows a formal dining etiquette in a more structured and refined atmosphere, concluding the meal with dessert. This starkly contrasts with the earlier scene, accentuating the class differences. The consumption of food is used here as a marker of cultural difference. Dining in the Shah household showcases wealth, sophistication, and refinement, which are absent in Rafi’s hovel. Miloni’s father, representing the middle class, has planned for her a career in accounting. In fact, she topped the CA foundation exam and is currently preparing for the CA Intermediate. Her father is trying to arrange her marriage with his friend’s son, who is going to the US to pursue an MBA. Miloni and Rafi, the protagonists of Photograph, hail from disparate social classes, yet they develop an affection for each other.

The more Miloni meets Rafi, the more she opens up to her domestic cook, who symbolizes Rafi’s social class. The cook’s anklets make Miloni think of the anklets she received as a gift from Rafi’s grandmother. Miloni observes these anklets attentively, fiddling with her spoons while dining on the table with her parents. She is inclined to communicate more with the cook and shows a growing interest in village life, reflecting Rafi’s rural origins. We cannot exaggerate the cook’s role in bringing Rafi and Miloni together. Though, she has seen Miloni being photographed with Rafi, yet, she does not report this to Miloni’s parents. She provides vital information to Miloni, which helps Miloni reject the arranged marriage her parents are planning. Before Miloni’s meeting with the boy selected by her parents, the cook remarks, “Sir and Madam were saying… this boy they want you to meet… He used to be fat. Now he’s thin. Meet him and see. What if he gets fat again? Think about it”. This comment subtly hints that an unbalanced diet, and thus food, could be a basis for rejecting the suitor. When Miloni meets her would-be husband in a restaurant, he offers her cake but avoids eating it himself as he is dieting. The brief conversation in the restaurant highlights their contrasting personalities even though they belong to the same class. Miloni yearns for a slow, pastoral life in a village, which may be a sign of her growing fondness for Rafi, whereas the boy prefers to live anywhere away from his parents.

Fig. 4 – Dining scene in the Shah household; still from Photograph (2019).

Miloni begins to indulge in street food, such as ice candy, with Rafi’s grandmother, relishing it freely. When she falls ill, her father scolds her in the doctor’s cabin. However, the doctor defends her, suggesting that regular consumption of street food will build her immunity to such infections. Ice candy thus transcends its role as mere food, becoming a symbol of class distinction. The question becomes: who can digest it and who cannot. The same ice candy has no negative impact on Rafi’s friend and grandmother, bringing the class difference to the fore. This symbol of class difference becomes a conduit for Rafi’s love, as articulated by Zakir Bhai: “Don’t worry, Dadijaan. My Ruksana was also very delicate. Her family pampered her a lot. After we got married, she adjusted to our circumstances. Her parents must have given her a comfortable life. The ice candy of Rafi’s love will get digested someday.” Hence, from a mere material entity, the ice candy becomes a metaphor. Miloni’s willingness to risk illness by eating ice candy signifies her attempt to bridge the class divide between herself and Rafi.

When Miloni visits Rafi’s home for the first time, she is offered deep-fried, piping hot, crispy pakodas. The scene is set against the backdrop of falling rain and the song “Noorie,” creating a romantic atmosphere. Rafi, who comes from a background of such poverty that he sometimes had to sleep on an empty stomach, is now working hard in Mumbai. His grandmother persuades him to forget the repayment of the debt and the retrieval of the village house. Rafi starts thinking of establishing a Campa Cola factory, a soft drink Miloni cherished in her childhood. Even Tiwari’s ghost endorses this idea. He was once a farmer in his village, but later took on low-paid odd jobs in Mumbai. His approval holds weight, as he probably could not match the social class of his beloved and tragically took his own life. Tiwari’s failure as a lover serves as a lesson for Rafi. The idea of establishing a Campa Cola factory symbolizes Rafi’s efforts to raise his status to be closer to Miloni’s social standing and signifies his love for her. Establishing the Campa Cola factory represents an attempt to revive the happy days of the past and bridge the class divide. As Terry Eagleton contends, “Food is just as much materialized emotion as a love lyric, though both can also be substitutes for the genuine article” (1). The narrative of the film includes the story of Sodabottlewala, a Parsi gentleman who purchased the formula for Campa Cola and started a factory at his home when it was disappearing from the market. He did all that simply to please his wife, who was fond of the drink.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the preparation and consumption of food acquire significant visibility in the films of Ritesh Batra, who intricately weaves his narratives around food. In The Lunchbox, the journey of the lunchbox plays a prominent role, reflecting the developing attraction between Saajan and Ila, manifested through their exchanged messages and shared experiences. Similarly, in Photograph, food serves as a crucial element, revealing character traits and deepening interpersonal connections, as seen through Rafi’s transformation and his interactions with Miloni. In these two films, the characters’ relationships with food reveal their identities and emotional journeys. Dining and food sharing are used to point out social connections, personal transformations, and cultural nuances. Dietary practices are closely connected to gender roles and class distinctions, as highlighted in The Lunchbox and Photograph. Women often transmit culinary knowledge and skills across generations, reflecting their roles in a patriarchal setup, while food consumption patterns reveal economic disparities and cultural differences between social classes.

While The Lunchbox can be categorized as a food-centric film, Photograph similarly employs food as a plot device, setting, and metaphor. However, there are specific reasons for considering only The Lunchbox as a food film. Lindenfeld and Parasecoli provide a definition of food films, stating: “First of all, food tends to function as a driving force in the films’ narrative structures. It connects the characters with each other and often emerges as a character itself. The protagonists are often domestic or professional chefs or at least individuals with strong connections to food and cooking. The camera spends a great deal of time focusing on images of strikingly beautiful food, which takes centre stage, bolstered by elements in the mise-en-scène” (15).

Unlike in The Lunchbox, food is not essential to the plot development in Photograph. Undoubtedly, it is an important element but not the focal point of the film. Although there are instances of food preparation in these two films, they do not emphasize the patriarchal appropriation of domestic labour as much as the aesthetic appeal of food. In Photograph, Rafi’s cousin prepares biryani for him and his friends, while in The Lunchbox, Ila, her mother and probably Deshpande Auntie dedicate considerable time to the kitchen. While it is known that Rafi cooks for his partner, it is intriguing to speculate on the kind of partner Saajan would become if he were to start a life with Ila. Would he be solely interested in consumption, or would he also engage in the preparation process?

References

Photograph, 2019, Directed by Ritesh Batra, Poetic License Motion Pictures.

The Lunchbox, 2013, Directed by Ritesh Batra, DAR Moton Pictures et al.

Barthes Roland, 1989, Sade, Fourier, Loyola, tr. Miller, Richard, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Bower Anne L., 2004, Reel Films: Essays on Food and Film, New York, Routledge.

Boyce Charlotte, 2017, “You are What you Eat?: Food and Politics of Identity (1899-2003)” in Charlotte Boyce & Joan Fitzpatrick, A History of Food in Literature: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present, London, Routledge.

Brillat-Savarin Jean Anthelme, 2009, The Physiology of Taste, Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, tr. & ed. Fisher, M. F. K., New York, Everyman’s Library.

Eagleton Terry, 24 October, 1997, “Edible ecriture”. URL: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/edible-ecriture/104281.article.

Farb Peter & Armelagos George, 1980, Consuming Passions, The Anthropology of Eating, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company.

Hemingway Ernest, 2014, “The Wild Gastronomic Adventures of a Gourmet” in Torronto Star Weekly, 1923 as quoted in Sandra M. Gilbert, The Culinary Imagination from Myth to Modernity, New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Kant Immanuel, 2006, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, tr. Laude, Robert B. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Klitzing Anke, 2019, « My Palate Hung with Starlight: A Gastrocritical Reading of Seamus Heaney’s Poetry” in East-West Cultural Passage, vol. 19, issue 2.

Lindenfeld Laura & Parasecoli, Fabio, 2017, Feasting Our Eyes, Food Films and Cultural Identity in the United States, New York, Columbia University Press.

Shakespeare William, 1901, Henry V, New York, The University Society.

Sanjay Kumar

Sanjay Kumar has been teaching French literature for the past fifteen years at The English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) in Hyderabad. He publishes in the field of French and francophone studies. He has translated four French novels and a play into Hindi and rendered a Hindi short story and a poem into French. Alongside two colleagues, he co-founded the journal Réflexions, which focuses on French and francophone studies. Recently, Sanjay Kumar published an article exploring the intersection of aesthetics, sound, and silence in Photograph, a Hindi film.

- Cet auteur n\\\\\\\'a pas d\\\\\\\'autres publications.